The Legacy of Thomas Francis Jr.

“Epidemiology must constantly seek imaginative and ingenious teachers and scholars to create a new genre of medical ecologists who, with both the fine sensitivity of the scientific artist, and the broad perception of the community sculptor, can interpret the interplay of forces which result in disease.”

—Thomas Francis, Jr.

The vaccine works. It is safe, effective and potent.

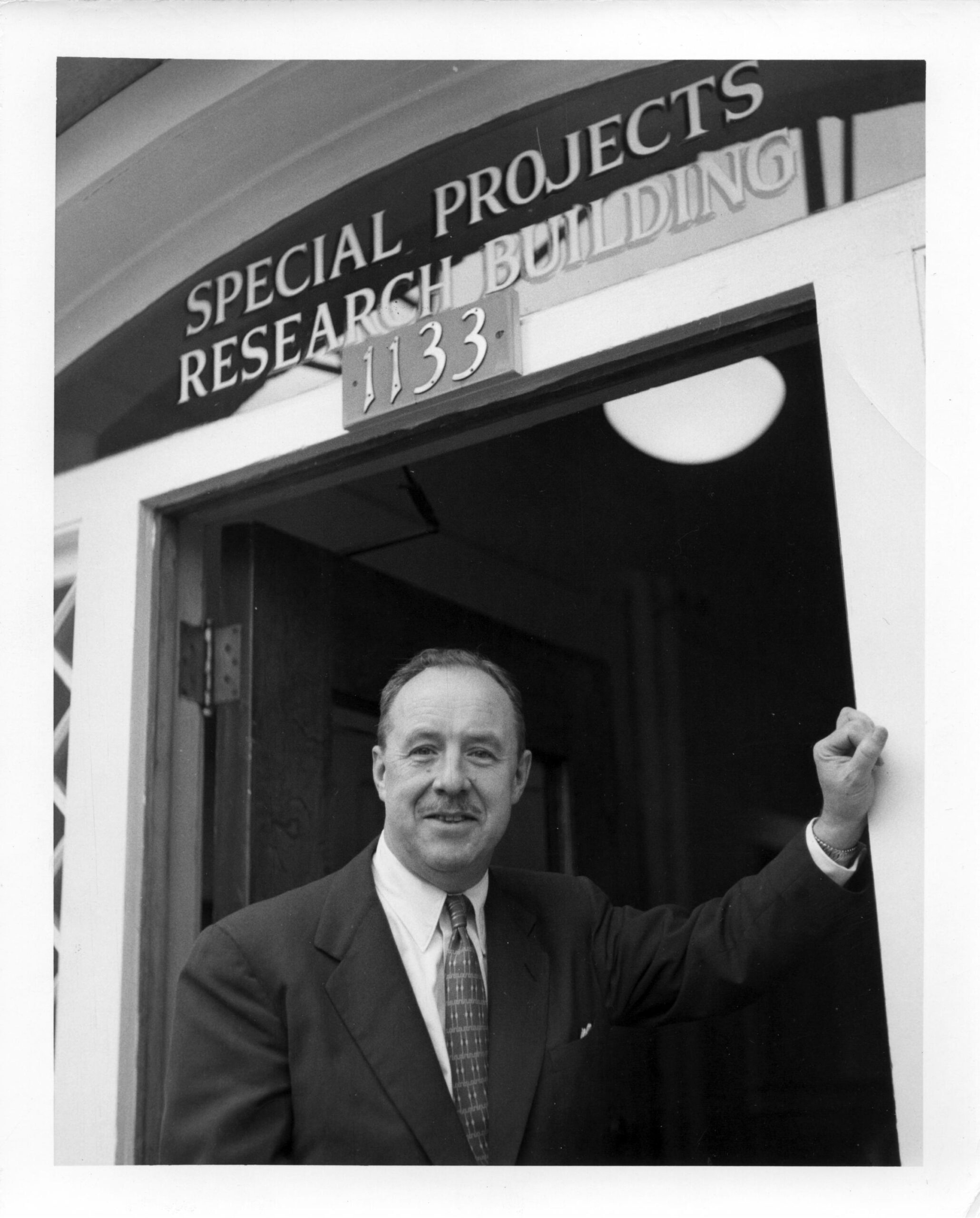

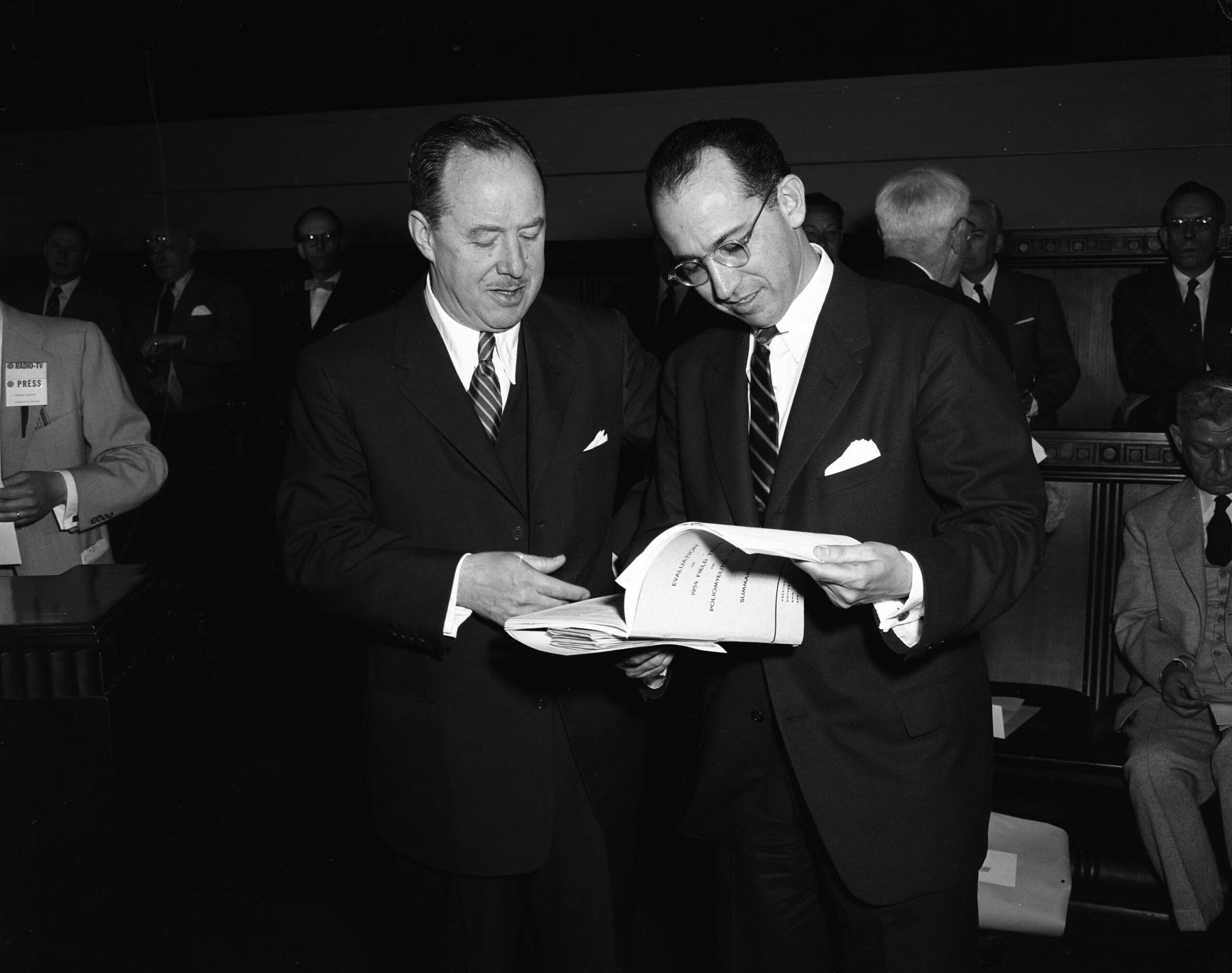

It was April 12, 1955, and Dr. Thomas Francis Jr., director of the Poliomyelitis Vaccine Evaluation Center at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, was announcing to the world that the vaccine, developed by his former student Jonas Salk, was protective of paralytic polio.

It had been decades since the paralyzing illness had been identified, and three years since 1952 when the worst wave in the United States had infected 6,000 children and killed 3,000. On average, the illness disabled 45,000 a year in the U.S. alone.

That day, the Rackham Auditorium at U-M was full of hundreds of journalists and medical experts from around the world as Francis announced the findings of the vaccination trials he had conducted on 1.8 million children from 217 areas in the U.S., Finland and Canada.

Within a decade, polio would be eliminated from the country and, eventually, from most of the world.

An innovating scientist with a focus on influenza work

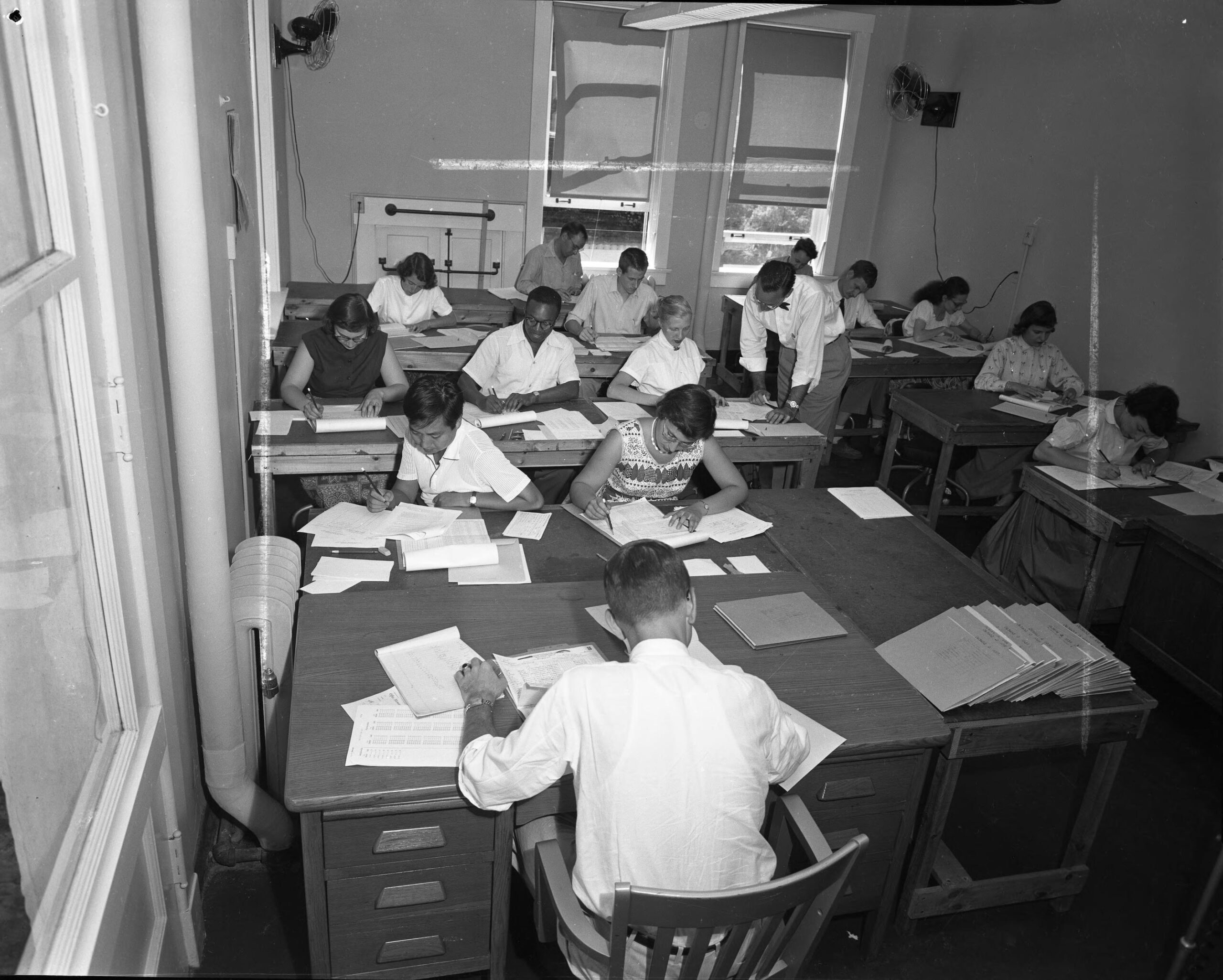

By all accounts, testing the polio vaccine was a feat of endurance, creativity and precision, and a real testimony to Francis’ scientific mind: Tens of thousands of handwritten records had to be evaluated under the most strict testing conditions to ensure scientific independence and accuracy. In scope and magnitude, it was unprecedented.

But Francis’ impact on global public health far exceeded this work, said Dr. Arnold Monto, who in 1965 was recruited by Francis to take on and expand the landmark Tecumseh Study. The study was one of the first large community-based studies in the country that would be used to test the herd immunity concept that is so familiar now.

“He felt his main contributions were with influenza research, coming up with the concept of original antigenic sin,” said Monto, referring to the idea that a person’s first influenza infection shapes their future response to infection. “That concept was developed at Michigan by Dr. Francis and his team. He also was the first one to identify influenza B. And with Salk, he developed the first inactivated influenza vaccine and did a clinical trial on that. So all these things were major contributions.”

The son of a steelworker and part-time minister, Francis was born in Gas City, Indiana, and grew up in western Pennsylvania. After graduating from Allegheny College on scholarship in 1921, and receiving his medical degree from Yale in 1925, he joined an elite research team preparing vaccines against bacterial pneumonia at Rockefeller Institute. He would soon take up influenza research.

By the time he was in his 30s, he was considered the leading authority of influenza in the U.S., according to historian James Tobin, who explored Francis and Salk’s work on vaccines.

In 1941, he was invited by Henry Frieze Vaughan to start the Department of Epidemiology at U-M’s School of Public Health. The same year, Francis was appointed director of the Commission on Influenza of the U.S. Army Epidemiological Board and took part in the successful development, field trial and evaluation of protective influenza vaccines.

At U-M, he built up the Department of Epidemiology that quickly focused on a broad range of infectious diseases. When Jonas Salk came to U-M in 1941 to pursue postgraduate work in virology, it was Francis who taught him the methodology of vaccine development. Salk’s work at Michigan ultimately led to his polio vaccine.

After the vaccine trials, Francis would start the Tecumseh Study, and eventually bring Monto in to look at the behavioral, environmental and family factors associated with cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions in a community over time.

“One of the things that people don’t realize is that he started this study to take advantage of the fact that he had brought people here to run the trial, and they were looking for something else to do after the trial was over,” Monto said.

Preparing for, and preventing, the next pandemic

Monto recalled that in 1968 Francis was traveling abroad when he sent his team in Ann Arbor an urgent telegram.

“It said something like ‘major influenza outbreak in Hong Kong. Local authorities uninformed,'” he said.

In Ann Arbor, researchers rushed to develop a vaccine and to look at the spread of the pandemic among 10,000 residents of Tecumseh and studied the outbreak, vaccinating school children. This work led to a better understanding of human herd immunity and continues today at the U-M Center for Respiratory Virus Research and Response that Monto and fellow infectious disease epidemiologist and School of Public Health professor Emily Martin co-direct.

The center, one of the five CDC centers tracking influenza across the U.S., became even more relevant when early in 2020, the World Health Organization declared SARS-CoV-2 a pandemic. For the past two years, Martin has worked tirelessly informing the public, the media and policymakers on COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

Francis’ work on influenza and pandemic prevention also continues to inspire others.

“The trials were huge but his life’s work was really understanding influenza, immunity to influenza and his research into the development of a vaccine,” said Aubree Gordon, associate professor of epidemiology at U-M’s School of Public Health whose work focuses on infectious disease epidemiology and global health.

She is the director of the newly formed Michigan Center for Infectious Disease Threats that seeks to leverage the wealth of expertise across the campus to solve critical problems related to the surveillance, diagnosis, treatment, and control of diseases caused by SARS-CoV-2 and other emerging pathogens. Her work has focused on understanding the transmission of influenza and its epidemiology in hopes to develop a universal vaccine.

“One of the issues with the influenza vaccines and with making a universal vaccine is we need to understand how the immune system will respond to a vaccine to antigens. And this concept of original antigenic sin, which Francis Jr. first described, it’s something we’re still trying to understand as we attempt to make a universal vaccine.”

Preparing for a global pandemic

As information about a new virus spread in late 2019, researchers across the university reached out to their colleagues from around the world to share knowledge and information on what was about to come.

Bhramar Mukherjee, the John D. Kalbfleisch Collegiate Professor of Biostatistics at U-M’s School of Public Health, and her team developed an app to describe the COVID-19 outbreak in India as well as providing forecasting models of the disease spread, information that has been used by both the government and the public at large to adapt as the pandemic continues to change.

In this work, researchers note, the rigorous testing, scientific reasoning and tenacity with which Francis Jr. conducted the trials and his vaccine research continues to echo.

“The legacy of Thomas Francis Jr. and his collaboration with Jonas Salk gives me a chill everyday as I walk into U-M’s School of Public Health building,” said Mukherjee, the chair of the Department of Biostatistics. “It makes me marvel at the magnificent effect public health can have on the world and what a privilege it is to be on faculty at our school.”